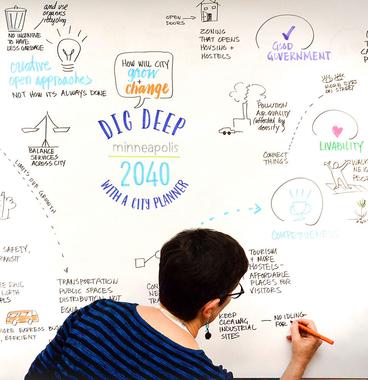

that developed the Minneapolis 2040 comprehensive plan. (Photo: David Turner)

By Susan Maas

Cities can and should tackle the hard problems. That’s the big idea behind Minneapolis 2040, an ambitious, far-reaching, and controversial plan to shepherd Minnesota’s largest city through the 21st century.

The comprehensive plan, which takes on systemic racism, homelessness, and climate change as it calls for up-zoning—increasing density and spreading retail more widely across Minneapolis—has received national attention since its release to the public last year.

And while its critics range from residents who reject its very premise to those who believe it doesn’t go far enough, most agree it’s unprecedented in its vision and scope. Among its key architects were Humphrey School alumni, all of whom share a propensity for thinking big. And way outside the box.

The Minneapolis 2040 plan effectively scraps single-family zoning districts–long considered the “third rail of land use planning,” says Paul Mogush (MURP '07), planning manager for the city and team leader of the group that developed the pioneering document. “Single-family zoning has been untouchable. And while that’s not the only important policy outcome of this plan, it makes complete sense that that’s what’s getting the most attention.”

But, he’s quick to add, “we did not start this process with that in mind.” Rather, city leaders began by asking: How might we help foster truly equitable growth in a city with a long history of overt discrimination and deep disparities in housing, education, and employment? And could we also promote resilience in the face of worsening climate change?

A Painstaking Process

Such questions spurred a different kind of planning process. Minnesota state statute requires municipalities in the seven-county metro area to update their comprehensive plans every 10 years. The plans must comply with the Metropolitan Council’s regional growth and development guide.

“In late 2015 we started talking with city leadership—elected officials and department heads—about broadly scoping this thing. There was an early consensus that we wanted to do much more than just meeting our statutory requirements,” Mogush says.

The three-year process of creating it was as thorough and deliberate as the document itself, Mogush says. “Out of those initial conversations, there was a steering committee formed by a city resolution to guide the broad strokes,” he explains.

Shortly thereafter, a dozen research teams comprising 170 city staff members from every department coalesced to gather information on quality-of-life topics ranging from housing to transportation to public health to environmental systems. The aim, he says, was to develop policy language that could move Minneapolis forward in each of those areas.

open house at Midtown Global Market. Photo: City of

Minneapolis

Community engagement was a top priority from the outset. Mogush had worked for the city during development of the previous comprehensive plan, and shared his colleagues’ belief that the document could be more thoughtful, expansive, and consequential than previous ones.

“This is really important work. In the seven years between when we had last done a comprehensive plan and were starting this one, my colleagues and I had done a lot of thinking about what we wanted to do better," he says.

Soliciting feedback from as many Minneapolis residents as possible would be paramount. They would need to be intentional about engaging people of all backgrounds and with a variety of perspectives to ensure everyone had a voice.

City planner and project coordinator Suado Abdi (MURP '14) helped lead outreach and engagement efforts around the plan.

“For me, community engagement is central. And I’m very passionate about making sure that it’s equitable, that historically underrepresented communities have a say,” Abdi says. “It was really inspiring. For us to start, at the beginning of this process, by talking with communities about historic discrimination and racial equity—to lay all of our cards on the table and say, this is where we’re coming from—was amazing. It made it OK for immigrant communities to come to the table and share their stories.”

Planners designed a process for soliciting public input that included holding public hearings and participating in neighborhood festivals and street fairs.

They attended Juneteenth, May Day, and Somali Independence Day festivals, where they talked with residents and invited written feedback. They had “Tweet with a Planner” lunch hours, in which city planners took questions and comments from the public via Twitter. Such events yielded ideas that made their way into the plan.

Among the comments they received were several articulating the need for small commercial spaces that would be cheaper and, therefore, more accessible to local businesses. One commenter suggested creating incentives for worker-owned and cooperatively owned businesses. That input prompted the addition of provisions in the plan related to developing affordable commercial spaces for small businesses and supporting the long-term tenure of commercial tenants in the community.

Mogush believes the plan would have been different without that degree of citizen engagement. “It was a lot of work and took a lot of resources, but it was absolutely critical. I’m pretty confident our city has never engaged the community on this level on anything before.”

Increasing Density

A chief feature of the plan is to allow development of duplex and triplex units in neighborhoods now zoned solely “single family,” thereby promoting housing density and, theoretically, affordability (The plan’s first iteration called for fourplexes; that was scaled back to triplexes in fall 2018). That change has been called radical by both detractors and supporters.

One of the issues that kept surfacing in comments from residents was the need for more affordable housing options. The population of Minneapolis has grown since 2000, and the demand for housing— particularly affordable housing—has outpaced supply. Moreover, the city has become majority renter in recent years.

housing options. Photo: City of Minneapolis

As planners learned about race and housing patterns (they attended a presentation on the Mapping Prejudice project, which documents historic housing patterns in the Twin Cities), they realized the affordable housing issue overlaid a more fundamental problem. The neighborhoods currently zoned exclusively “single family” are also the most uniformly white neighborhoods in Minneapolis.

That’s no coincidence, Mogush says. It stems directly from the widespread use of housing covenants designed to keep people of color out of certain areas. Those covenants, combined with the longstanding practice of “redlining” or racial discrimination in mortgage lending, largely account for the de facto segregation that pervades Minneapolis today.

Andrea Brennan (MPA, '97), the city’s director of housing policy and development, says the cause of the segregation was clear. “We didn’t get here by accident,” Brennan says, “and we’re not going to get to be a more equitable city by accident, either.”

That aspect of the plan sparked controversy right off the bat. Although many public comments were positive, critics were vocal and organized. A group of opponents calling itself Minneapolis for Everyone began distributing "Don’t Bulldoze Our Neighborhoods!" signs to opponents in mostly well-to-do areas with high rates of home ownership. Foes of the plan decried it in public hearings as a misguided "social experiment" that would "change the character of our neighborhoods forever."

The planners listened to both sides. “We received well over 10,000 comments. We actually read all of them, and that was not an easy task,” Mogush says. “Many were genuinely helpful, and it was gratifying to incorporate new ideas and improvements. And some were vitriolic and racist.” For transparency’s sake, staff made changes to the document visible to the public. “We’ve shown our work. [Updates] have happened gradually and iteratively.”

Not all critics of the plan rejected its core principles. Some believed it didn’t go far enough—or worried that just increasing density might not enhance affordability but actually further erode it. One frequently expressed concern was that the plan could simply enrich developers by opening the door for them to build more expensive, high-end “boutique” rentals and condos where single-family homes once stood.

“It’s absolutely true that density alone doesn’t create affordability–we would never purport to say that,” Mogush says. “What we do say is that increased density and increased housing supply is a necessary prerequisite to affordability. There’s no getting around the fact that actually building more affordable housing requires pretty substantial subsidy.”

To that end, Mayor Jacob Frey’s 2019 budget included $40 million for subsidizing affordable housing. And in December, the Minneapolis City Council approved an inclusionary zoning provision that would require a certain percentage of new units to be affordable.

Mitigating Climate Change

Minneapolis 2040 includes numerous measures to address the growing threat of climate change. Among them: eliminating minimum parking rules that require developers of condo and apartment buildings to provide a limited number of parking spots, thereby encouraging walking, biking, and transit use. And it allows for more commercial districts around the city, a provision that aims to decrease residents’ need to drive.

The hope is that the reduced need will result in fewer vehicle miles traveled. “Nationally, nearly half of car trips are for running errands. And in Minneapolis, when we run our errands, we generally aren’t taking the bus or train to do that; we’re driving cars. We have a lot more demand for retail than we have supply in the city. This is an opportunity to replace or shorten car trips by making it easier for retail to locate inside the city,” Mogush explains. “More residents will be able to walk to the store, or take the bus to the store—or at least have a shorter driving trip.”

Kelly Muellman (MURP '11), a sustainability program coordinator with the city, says the plan doesn’t just swing for the fences on climate change mitigation and adaptation; it does so in a “holistic” way that reinforces city goals of racial equity and improved livability for all.

To take one example: 2040 policy No. 65, supporting urban agriculture and local food production, could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions (with fewer “food miles” traveled and less carbon-intensive storage and processing), while boosting community food cultures and local entrepreneurship. “It’s not just traditional environmental issues,” Muellman says of the plan’s climate components. “It really touches on everything.”

Awaiting Approval

The plan was submitted to the Metropolitan Council at the end of 2018, with approval anticipated sometime later this year. But the work is just beginning. Implementation will be long, complex, and challenging in ways both predictable and unforeseeable.

“We’ve laid out our ideals of what we can achieve over the next decade. But if there’s no one to stand up and fight for [a particular aspect of the plan], it’s not going to happen,” Muellman says. “We need the community to hold the city accountable to these commitments.”

Still, city planners are justifiably proud of their work. Indeed, helping create such an innovative and pioneering document is a major achievement. And the plan reflects the mark of the Humphrey School, as so many alumni worked on it.

“At the Humphrey School, you don’t learn the mechanics of how to be a planner, you learn how your work affects social outcomes,” Mogush says. “We are driven to improve social outcomes in our city.”

THE ARCHITECTS: Some of the Humphrey School alumni who helped shape Minneapolis 2040

- Paul Mogush (MURP ’07) managed the project

- Kelly Muellman (MURP ’11) worked on the environmental systems research team

- Andrew Dahl (MPP ’13) provided economic competitiveness policy analysis

- Andrea Brennan (MPA ’97) led the development of housing policies and the effort to implement an inclusionary zoning policy

- Wes Durham (MURP ’16) developed the interactive maps that are at the core of the plan

- Joe Bernard (MURP ’07) led the process to create the Land Use and Built Form maps and policies

- Suado Abdi (MURP ’14), Mei-Ling Smith (MURP ’12), Kadence Hampton (MURP ’14), and Antonio Rosell (MURP ’01) worked on community engagement

- Aaron Hanauer (MURP ’06) worked on the land use team

- Darrell Gerber (MS-STEP ’06) worked on the environmental systems research team, as a member of the Minneapolis Community Environmental Advisory Commission

- Michael Peterson (MPA ’13) provided housing policy analysis

Susan Maas is a Minneapolis-based freelance writer and editor.