Amidst the unusually warm weather this winter in Minnesota and around the world, the ongoing discussion over the effects of climate change is heating up as well.

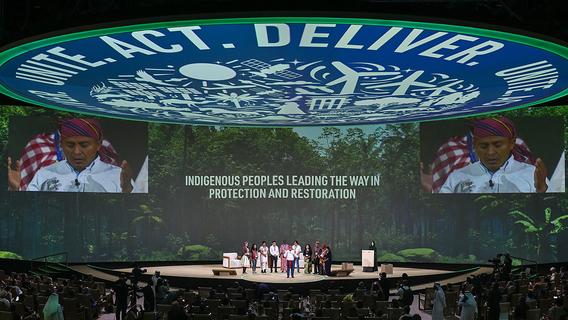

The global community took some new steps toward solutions during the annual United Nations International Climate Change Conference (known as COP28) in Dubai late last year, and more than two dozen representatives from the University of Minnesota got an up close look at those discussions.

They attended international negotiating sessions, lectures, and presentations, along with tens of thousands of people representing nations, states, cities, nongovernmental organizations, and private companies, or just observing, at the conference.

Some of the attendees, including several from the Humphrey School of Public Affairs, reflected on their experiences at COP28 at a recent panel discussion. One of their main themes was the unequal power dynamics between developed and developing countries, and how that played out in the resulting agreements from the conference.

That issue was at the forefront of the University’s process for choosing participants to send to COP28. Applicants who have a connection to a developing country, through family or work ties, were given higher priority.

Here are some key points from the conversation.

Creation of the Loss and Damage Fund:

Delegates at COP28 agreed to establish a Loss and Damage Fund, which will provide financial support for developing countries to help them recover from the harmful impacts of a changing climate—such as floods, drought, and sea-level rise—that they have done little to cause.

Developed countries in the global north, including the United States and European nations, have pledged millions of dollars toward the fund. But the panelists said that commitment is far too small to make much of a difference. While the anticipated need is in the hundreds of billions of dollars each year, the United States’ initial pledge is just $17 million.

Humphrey School alumnus Nfamara Dampha (MDP ‘17/PhD NRSM ‘20), a research scientist at the University of Minnesota's Institute on the Environment who represented his native Gambia at COP28, noted that developing countries have been pressing for a loss and damage fund for nearly a decade. Dampha said he is disappointed that the agreement doesn’t hold polluting nations more accountable.

“Developing countries wanted language that would hold developed countries liable and responsible for climate-related damages, specifically. But developed countries made it clear that they are not going to accept that liability,” he said. “Basically, they said, this is going to be through cooperation and facilitation, meaning, ‘We're going to give you what we can. But we are not going to be held liable and responsible for this.’”

The responsibility of the private sector:

Muneeb Hafeez, an MBA candidate at the Carlson School of Management, noted that large corporations responsible for producing much of the climate-altering greenhouse gases are not being held accountable in the COP agreements.

“I feel that the private sector and the global corporations that are making these negative contributions to the environment should also be contributing to the loss and damage fund,” Hafeez said. “It is not just the taxpayers of the global north that should have to contribute. And I felt that was a conversation that was just missing at COP28.”

Climate change and human rights:

It may seem logical to consider the consequences of climate change as human rights issues for the populations involved, who may experience food or water scarcity because of drought, or lose their homes in floods or catastrophic weather events. But the words “human rights” were absent from the COP28 discussions, according to Master of Human Rights student Natika Kantaria.

“For instance, when there was a talk about food scarcity, there was no mention of the right to have food or access to water. There was no mention that there is a right to sanitation. They did not mention that climate change consequences have a direct impact on economic, social, and cultural rights of people around the world,” she said. “I would like to see more environmentalists and scientists advocating for human rights. We lack understanding of how the two areas are intertwined.”

Hopes for the future:

Danielle Sindelar, an urban and regional planning student at the Humphrey School, participated in COP28 virtually. She said she is hopeful that more local governments will press ahead with their own climate solutions.

“In the online COP, there were mayors from cities around the world sharing some of their current local policies … to push their own climate goals,” Sindelar said. “I think that cities have the capacity to do more than their countries are trying to do right now.”

Samuel Makikalli, a second-year Law School student, said he hopes climate change remains a top priority for the global community.

“COP is a two-week stretch every year where everyone pays attention to the issue. But that dries up after the conference ends. I hope we, as members of the academic community and civil society, can maintain attention on these issues.”