The “dual pandemics” of COVID-19 and structural racism have hit African American individuals and communities particularly hard over the past two years, as racial inequities in income, employment, and health care affecting people of color were exacerbated when the pandemic hit.

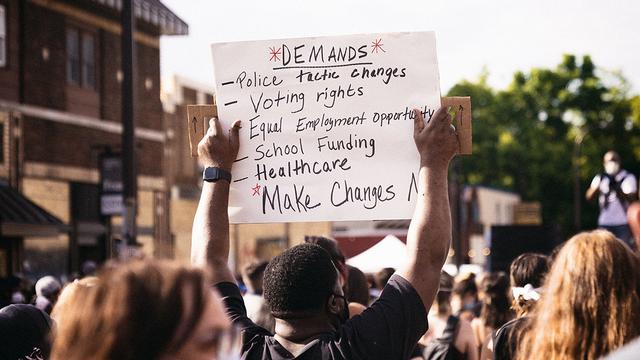

The May 2020 murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police, and the subsequent protests calling for change, brought these two converging crises into dramatic focus.

The Humphrey School of Public Affairs hosted an online discussion on February 28 to highlight some of the policies that have racially disparate effects on African American individuals and communities, and how they can be addressed.

Panelists were Humphrey School doctoral candidate Rashad Williams, whose research focuses on Black political thought and urban planning; alumnus Denetrick Powers (MURP ‘18), co-founder of urban planning and real estate firm NEOO Partners; and Shawntera Hardy, co-founder of Civic Eagle.

Here are some excerpts from their conversation, edited for length and clarity:

About their current work:

Denetrick Powers:

I'm a planner, and often I hear other planners say they are stewards of the built environment. But I'm very much a planner of the social environment, which is why I chose to focus on sociology and entrepreneurship during my time at the Humphrey School.

I started NEOO three years ago to transform the way business is done, especially for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) small businesses. We help connect them to resources and help them find spaces that are suited to their business. Over the last year, I led some strategy development around small business incubators and accelerators. We also lead community engagement efforts for different types of projects that are focused on economic development.

Shawntera Hardy:

As we think about public policy and the damage that many of the policies have created in BIPOC communities, we aim to bring forth policy that truly gets to shared prosperity and contributions in where folks work, live, and play. Civic Eagle is building cutting-edge software to allow for public policy to be discoverable, to be collaborative, and to make sure that it is accessible to all.

There are more than 400,000 jurisdictions in the United States on the city, county, township, and state levels that establish various policies that affect all of us. Our team works to build better tools, to provide better access to the politics and policies that impact us.

Rashad Williams:

I'm interested in why racial inequality persists. I'm interested in reparations for African Americans, because I see it as a very important way of working within the intersection of social and political theory to undo what we all should recognize: Wealth begets wealth, poverty begets poverty.

Of course there are exceptions, but the pattern of dependence has been laid through policies that have excluded Blacks for so long, such as the New Deal, redlining, racial zoning, sundown towns, and so forth. We’re still dealing with those effects today.

As an urban planner, I'm interested in reparations on a municipal scale, what I call “reparative planning.” We should think about reparations as a national program, but there have been some successful experiments with reparations at the municipal level.

On how the current social atmosphere can inform urban planning and community development:

Denetrick Powers:

The first thing is understanding that learning happens best in an environment where dialogue is shared, power is shared, and spaces are shared.

As planners and leaders of local governments, we have to listen. I think people are saying exactly what they want to see changed, and they aren't waiting for the government to make decisions. Communities are having dozens of meetings trying to really figure out what it is that they want, and they've come up with some very tangible ideas.

We can’t keep approaching any project with the idea that the city council or the mayor has more power than the community they're supposed to be planning for.

These are people who care about their community, their neighbors, their families. They’re folks who don't come from a traditional economic development policy or planning background. So we need to remember that leadership comes in many forms, and we shouldn't pass judgments just because somebody doesn't have a degree, or because somebody isn't an organizer in the traditional or formal sense.

Folks are creating space. They aren't just taking that space by protesting, they're creating space for new dialogue to happen, for new ideas to happen.

On improving support systems for communities of color:

Shawntera Hardy:

One of the mantras that guided my work when I was the city planner for the city of St. Paul is this quote: “If you listen to the whispers, you won't have to hear the screams.”

Over these last two years in particular, we've heard the hollering of our systems. In reality, they've been very loud for a very long time, especially for communities of color. Now, more people are listening to folks telling what they need – that's the power in creating a system that's going to actually help people to get what they need and what they want..

For example, we are so comfortable now with virtual health care – telemedicine – and shifting policy to ensure folks are actually getting access to the health care that they need. We have to ensure that we are not baking the same biases and policies into our health care system in this new virtual space that we have done in the office setting.

We need to make sure that we are shifting policies to meet people where they are, to ensure that we're building infrastructure that's going to make sense, that we are building education systems that take into account all the languages that are spoken in our schools, that we are being honest about the under capitalization of small businesses in our community, which are the backbone of our economic system.

[We also need to ensure that] folks who have direct connections to the community get the opportunity to take their experience into Congress, the Legislature, the city council chambers. What we see is that some folks are not comfortable with that type of representation, when individuals that have been on the ground are actually pushing public policy. I think there's this need for us to shift not only the language, but the representation and the access to public policy.

On barriers to addressing reparations at all levels of government:

Rashad Williams:

We have seen some success with states putting forward reparations for specific moments or incidents of harm.

For example, the Florida Legislature, in 1995, gave reparations to the surviving victims of the Rosewood race riot of 1923, when the entire Black town of Rosewood was burned to the ground. A number of individuals were murdered. The wealth that they did have was completely erased. Some 60 years later there was an apology, and each member of the community or their survivors [received a monetary award].

Think about the kind of harm that does, not just at the moment, but also intergenerationally. If there’s a loss of any kind of wealth-building potential or a major setback that has implications for generations to come, then the solution is to do something about the material disadvantage that this grouping is encumbered by [which means monetary reparations].

On a local level, some cities are examining the idea of reparations. But the bill for reparations far exceeds what any city, or even all cities in the aggregate, would be able to pay. If you add up the budgets of all the cities across the country, you get a total of around $2 trillion. But the bill for reparations far exceeds that.

If we use the estimate of the promised 40 acres and a mule [to formerly enslaved people at the end of the Civil War], or if we think about what would be required to close the racial wealth gap, estimates of reparations range from $2 trillion to $16 trillion.

But we also need to consider the policy question: What exactly are we trying to resolve through reparations? How do we understand the nature of the harm? If the harm is a free-floating kind of cultural harm, then the policy solution may be just an apology.

On the federal level, it's intransigence that Congress has not acted on HR 40, a bill that was proposed by John Conyers in the late 1980s to just study reparations. And we can't even get this through.