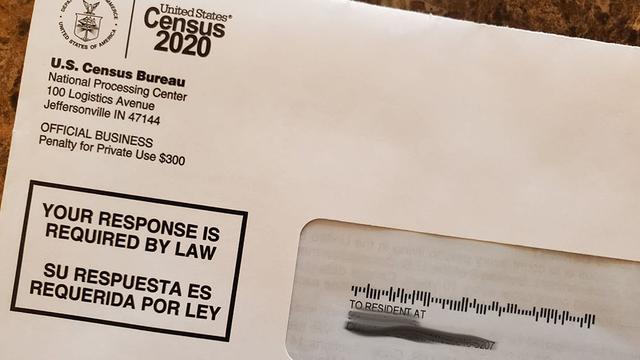

instructions on how to fill out their census form.

Today is April 1; it's officially Census Day. Every 10 years, the U.S. Census Bureau works to count every person who's living in the United States.

The final population numbers will guide the distribution of billions of dollars in federal and state funding and determine political representation for the next decade.

The population of the United States was 308,745,538 based on the 2010 census, an increase of 9.7 percent compared to 2000.

By now every household in America should have received a mailing with information about how to fill out the census online, by mail, or by phone.

This year’s census efforts are being affected by the coronavirus outbreak and the restrictions on in-person contact, so some deadlines have been extended.

Assistant Professor Janna Johnson of the Humphrey School of Public Affairs is an economic demographer and an expert on the census. She shares her insights on how the census is working to get the most accurate count this year.

Why is April 1 so important?

April 1 has been considered ‘Census Day’ for the past 90 years. The census aims to count everyone who is living on U.S. soil on April 1, 2020, whether they’re here permanently or temporarily. That includes people who are homeless, international students studying at American schools, and foreign nationals residing in the U.S. It has nothing to do with whether you’re a citizen or a permanent resident. It's ‘Are you living in the United States on April 1?’

What is the Census Bureau doing to respond to the coronavirus outbreak?

The original plan was to have all the census data collected by July 31, but the bureau pushed that deadline back to mid-August. The bureau will take any other steps it deems necessary to ensure an accurate count, even if it means further delays. The Census Bureau is required by law to deliver the census results to the President and Congress by December 31. If it’s necessary to delay this date I'm sure it will be addressed, although it would likely require congressional action.

There’s concern about undercounts of certain groups of people, especially communities of color and immigrants. What factors are at play?

A lot of it has to do with a lack of permanent places of residence. It’s harder to count someone if they don’t have a place they call their home, where they can receive mail, etc. It’s also harder to count people who want to avoid contact with government representatives, even though there are strict laws in place that protect census responses from being used for any other purpose. For undocumented immigrants or people with criminal records, that can definitely be a factor.

Native Americans living on reservations have historically been undercounted as well, again, due to a trust issue or a lack of permanent addresses. In some ways it’s easier to reach those populations because we know where the reservations are, whereas in areas that have other hard-to-count individuals, such as large urban areas, they may not be as easy to identify.

People without a permanent address are harder to reach, but they still need to be counted. There will be a specific outreach effort to count homeless people between April 29 and May 1.

Who is most likely to be undercounted in the census and why?

There are two groups that are consistently undercounted in the census: children under the age of 5 and African American men. For African American men, it’s because they are less likely to have a permanent address. They might be splitting time between houses or have a fluid housing situation.

Some people think that’s because a higher proportion of African American men are incarcerated. But that’s not the case, because prisoners are easy to count. People in institutions and long-term care facilities are also easily counted; we know where they are.

As for the young children, we don’t know why we miss so many of them. And that pattern shows up across racial and ethnic groups. In my research, I’m analyzing birth and death records of native-born children in that age group to try to figure out how many of them we’re missing in the census, and why.

What are the consequences for communities where there is an undercount?

A lot of funding allocations for federal programs that help the underserved are based on census counts. So populations that could benefit the most, such as communities of color, immigrants, and so on, could lose out on these assistance programs if they’re not counted accurately. States and local governments also use census data to make decisions about funding of other programs and policies; highway funding is just one example.

You’re involved with the Census Bureau’s analysis of undercounting. What does that entail?

I’m an external subject matter expert for the Demographic Analysis Program. It’s a method the bureau uses to try to measure undercount that involves forming an estimate of the population independent of the census counts. It uses birth and death records, and other records that can measure immigration, to try to come up with a population estimate on April 1, and then that estimate is compared to the numbers from the actual census.

What happens if your analysis turns up an undercount in this year’s census?

Not much. The last census that was known to have a bad undercount was 1990. There were court challenges asking for the count to be adjusted, because it affected federal funding and things like that. The result of all that litigation was that they didn’t adjust any of the census results because it was just too complicated.

The demographic analysis is still valuable, though. We want to know if there’s an undercount and what it looks like, so we can measure the accuracy of the census and learn lessons for the next time.

Is there a problem with overcounting, too?

It certainly doesn’t get as much attention, but overcounting tends to show up in certain populations; college students, for example, because they’re counted where they’re living for college, and often their parents also put them on their form back home. They should only be counted once, where they are actually living on April 1.

Many college students are back home with their parents now due to the coronavirus outbreak. How should they respond to the census?

In most cases students living away from home at school should be counted at school, even if they are temporarily elsewhere due to the COVID-19 pandemic. So students staying with their parents due to pandemic-related university closures should NOT be counted on their parents' forms. If they reside in on-campus housing, they will be counted through Group Quarters Operations. If they reside in off-campus housing, but are currently at their parents' home, they should be counted at the address they reside at when they are at school.

What is the role of census enumerators?

Enumerators are really key to getting an accurate census count. They are the people who go around door to door to follow up with residents who haven’t filled out their census form by a certain date. The bureau wants enumerators who speak the language or are of the same ethnic background as the neighborhoods they will be assigned to. People with the appropriate language skills and cultural competency can interact with those community members, and address the trust issues that could result in high undercounts.

How could their work be affected by the COVID-19 outbreak?

Since the situation is rapidly evolving, it’s hard to say what the impact will be. On one hand, as individuals are encouraged to stay in one place due to the outbreak, this may make it easier to determine who was living where on April 1. On the other hand, since enumerators won’t be sent into the field for several months, after stay-at-home guidelines are relaxed, individuals may not remember who was living where on this date. Regardless, it is even more important now that individuals respond to the census online, by mail, or over the phone to prevent the need for enumerators to (eventually) have to go door to door.

In Minnesota there’s concern that we could lose one of our eight congressional seats depending on the census outcome. How likely is that to happen?

It’s not a sure thing. Based on the projections, we’re on the cusp. The formula that’s used for apportionment is very complicated, so it’s really hard to say at this early point. It will depend on what our population count is compared to other states that are also close to losing a seat.

More information: