New research led by the Humphrey School of Public Affairs sheds light on the origins of racial disparities in the Minneapolis park system and their long-lasting consequences for environmental justice in the city.

Rebecca Walker, a PhD candidate in urban planning at the Humphrey School, is lead author of the study, “Making the City of Lakes: Whiteness, Nature, and Urban Development in Minneapolis,” which was published recently in the Annals of the American Association of Geographers.

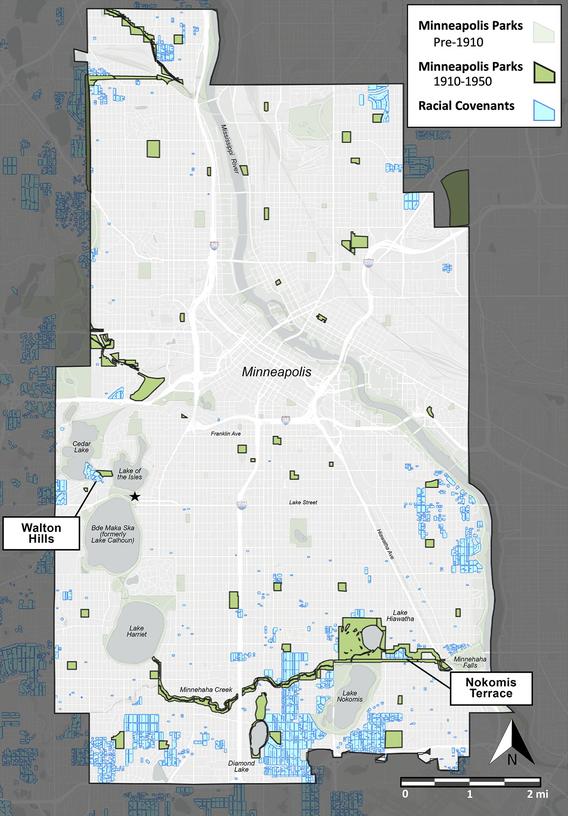

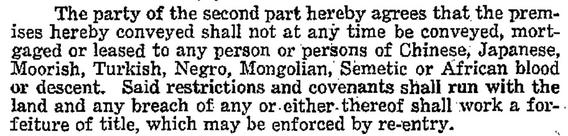

The researchers drew on maps from the U of M Libraries Mapping Prejudice Project, including a map of properties with racial covenants — clauses included in property deeds that prevented sale to anyone considered not white — to uncover the intertwined history of racial housing segregation and Minneapolis’s park system.

The study combined the covenants map with archival research about the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.

The researchers also combed through historic meeting minutes, newspaper archives and property records to understand why so many of Minneapolis’s parks were built in neighborhoods with racial restrictions.

Key findings:

- Throughout the first half of the 20th century, real estate developers partnered with the Minneapolis Park Board to build new parks in neighborhoods blanketed with racial covenants that restricted occupancy to “Whites Only.” To direct public investment into those neighborhoods, developers donated land for new parks or offered to contribute to the costs of building a new park.

- To market their developments, real estate developers in Minneapolis relied on the strategy of pairing “greenness,” investments in urban parks and gardens, with “whiteness,” ensured by adding racial covenants to properties. The result: during the 45 years from 1910 to 1955 when covenants were used in Minneapolis, 73 percent of new park areas had at least one racial covenant within one block (0.1 miles) of the park.

- Links between the Park Board’s disproportionate investment in parks in majority-white areas of Minneapolis and racial disparities in environmental quality are still present in the city today. Neighborhoods that historically had racial covenants today have higher tree canopy cover, more park acreage, and cooler temperatures.

"This research shows that disparities in the Minneapolis park system weren’t an accident — parks, race, and real estate have always been deeply intertwined,” said Walker. “Making an equitable park system means not just investing in greenspaces in historically disinvested neighborhoods, but also making sure that the right housing policies are in place to protect low-income residents and people of color. The City of Minneapolis and the Park Board need to step up to this challenge."

While this study focused on Minneapolis, the authors point to evidence suggesting that this was a nationwide phenomenon. For example, the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ 1924 code of ethics stated that “a realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to the property value in that neighborhood.”

"Understanding the historical context that gave rise to the current distribution of wealth and nature in cities is essential in identifying policy and planning solutions that address persistent disparities," said Bonnie Keeler, associate professor at the Humphrey School and study co-author. "This research demonstrates the importance of considering the past as we aim to create more equitable urban futures."

Additional co-authors are Assistant Professor Kate Derickson and postdoctoral researcher Hannah Ramer, both in the geography department in the College of Liberal Arts.

The project was supported by the National Science Foundation Long-Term Ecological Research, Minneapolis-St. Paul.